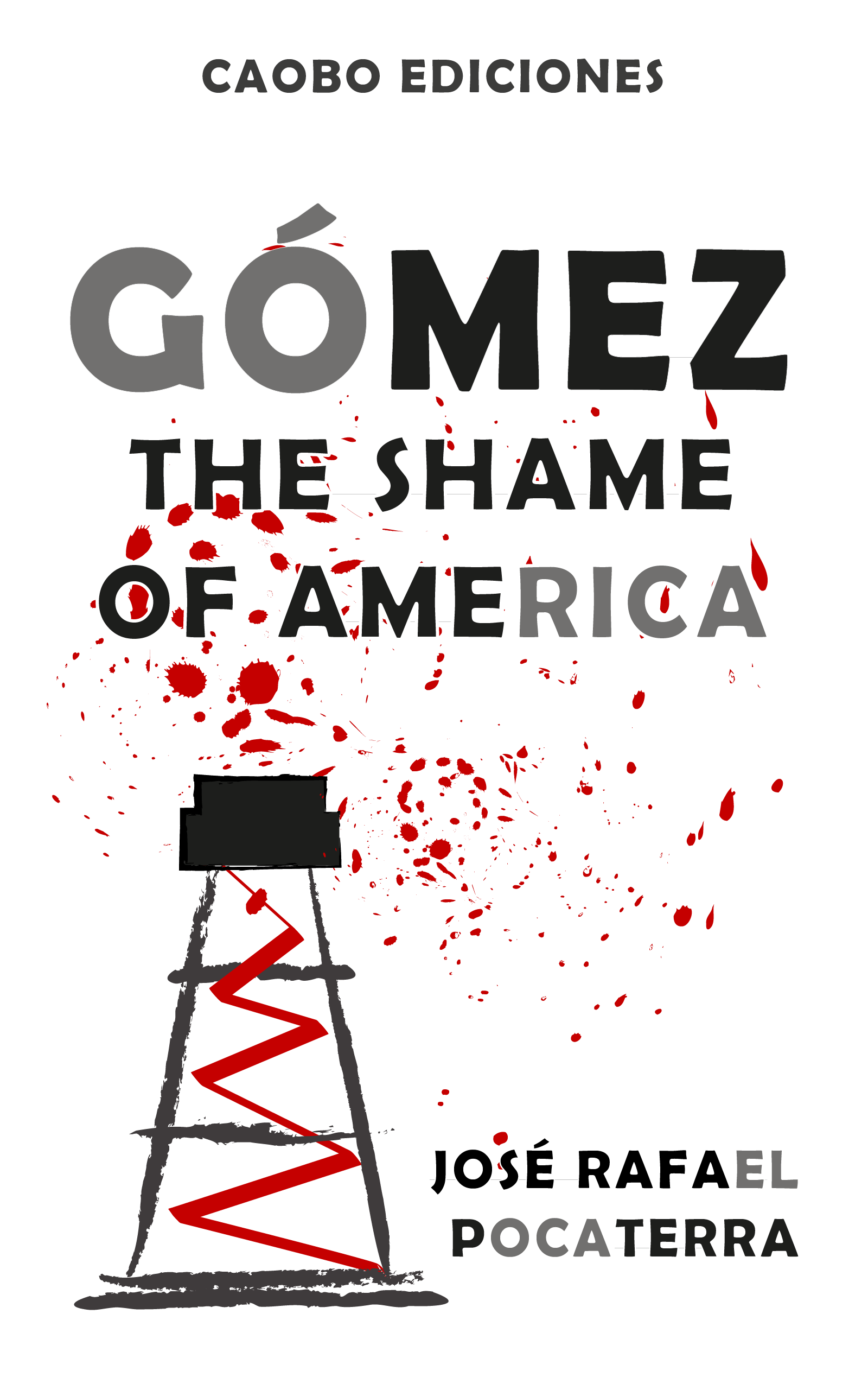

Gómez, the Shame of America

€ 2,99

The age of oil in our western society starts traditionally in the 1950’ies, but it rather ignores the effects on the discovery of the black gold in the countries where it originated. José Rafael Pocaterra describes with the sharp and crystal clear tone we know him for the incursion of the foreigners on Venezuelan land, the effects of the vast new income on the Venezuelan regime and then, in the form of his prison diary, how this regime deals with those who oppose them.

The author wrote this book from the jail for political prisoners of Caracas La Rotunda. Fearing for his life, he smuggled the manuscript out on small papers hidden in matchboxes. It was first published in New York anonymously, while he himself was still in jail, with the goal of gathering international support for the opposition against dictator Juan Vicente Gómez.

The clear descriptions and flowing story quite often feel like fiction. As a precursor of the style of New Journalism, not even the horrors of La Rotunda could soften Pocaterra’s pen or take away the humor and lightness which are so typical of Venezuelan culture. We hope you find in this book the inspiration you need and the fire that the author wanted you to have.

Other formats and stores

(paperback)

José Rafael Pocaterra

journalist, writer, political activist

José Rafael Pocaterra lived in Venezuela in the first half of the 20th century. He was a journalist, writer, and political activist who fought against the dictatorships of Cipriano Castro and Juan Vicente Gómez in Venezuela. During that period, he spent several years in prison, including in the infamous Rotunda prison. Later, in 1929, he participated in the failed coup attempt, the so-called “Falke” expedition, organized by General Delgado Chalbaud, whom he had met in prison.

In 1939 he became Minister of Communications under the government of Eleazar López Contreras, and later held various positions of ambassador. Following the assassination of Carlos Delgado Chalgaud in 1950, he resigned as ambassador to the United States. He passed away in Montreal in 1956.

Throughout his life and travels, he continued to write. His most famous works are his memoirs, as well as the series of short stories in social realism style about life in Venezuela, many of which focus on his hometown of Valencia.

Extract

Porras Bello was among these survivors. This was already very inconsiderate of him and by way of aggravating his offense and in spite of the seventy-five pound grillos he was obliged to drag about with him, this hardened reprobate managed to break the rules of the establishment. He actually supplied remedies and food to those who were ill. He also washed their sores and nursed their attacks of fever, to say nothing of securing, by some trick known only to himself, certain comforts from Governor Mediana, from whom it was as difficult to obtain a dose of bicarbonate as an ounce of pure radium. During the influenza epidemic, when practically all the prisoners were ill, Bello, ruffian that he was, connived with Arevalo his accomplice to attend to the washing of the seventy-odd bedpans of his companions. Such criminals always find acolytes to aid them in executing their misdeeds.

All at once I caught sight of an extraordinary figure crossing the courtyard. Is it a lunatic or a man in fancy dress? He wears a bath-robe and his black, curly hair falls to his waist. The bar of his grillos is so heavy that he drags them along on a little wagon the wheels of which are made out of spools of thread. He stops for a moment, bows pleasantly to the group of men warming themselves in the sun and raises his head. Now I recognize him. He is Román Delgado-Chalbaud.

Delgado-Chalbaud was arrested on May 17, 1913. At that time he was President of the Compagnie de Navigation Fluviale et Côtière. One hundred and fifty-seven other men were arrested at the same time. Fifty-seven were thrown into the dungeons of the fortresses of Puerto Cabello and San Carlos, fifty remained at La Rotunda; others were freed one by one after having been confined for periods ranging from three to six years. At the time of which I am now writing seven were still alive and at La Rotunda, Román Delgado-Chalbaud, the famous preacher Father D. Antonio Luis-Mendoza, the lawyer Nestor Luis Pérez, and Colonels M. Delgado-Chalbaud, Carlos Iru and Ramon Parraga.

The last named officer was paralyzed but nevertheless chained with a pair of grillos. Those worn by the Delgado-Chalbaud brothers and the aged General Avelino Uzcategui, who had been locked up about the same time on account of the personal dislike of Gómez, weighed eighty-five pounds apiece. The former governor, Luis Duarte Cacique, had tortured these prisoners by shutting them up naked in cells of which the pavement was daily flooded to a depth of several inches. Double curtains were nailed over the doors so that neither light nor air could get in and for years they were kept on a starvation diet. The only way they managed to survive was thanks to the self-sacrifice of their companions who passed them some of their own scanty supply of food.

This was done in spite of the cruel watchfulness of the jailors, all convicted criminals who had been specially chosen from the lowest class of convicts. One of the most notorious of these wardens was a culi, a Hindu who had escaped from one of the islands of the Antilles near Trinidad and whose ferocious instincts had appeared after he had been betrayed by a woman. When asked why he was in prison he always gave the same answer: “Woman deceive me. I kill woman. I kill son. I kill mother of woman. I kill dog. I kill cat. I not kill parrot because it fly away.”

This was the type of man who was put in charge of the prisoners imprisoned for political offenses.